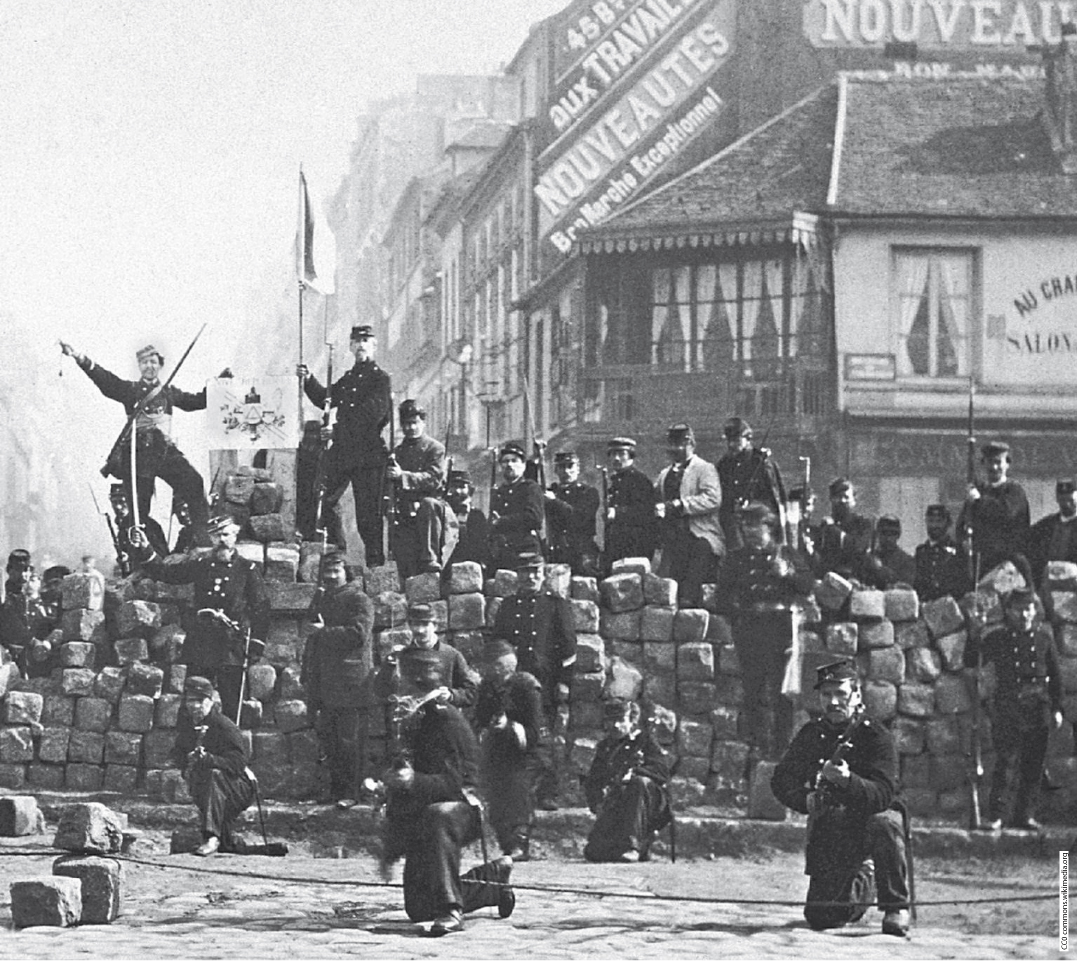

Barricade on Rue Belleville. It blocked the way to the workers’ district of the same name and was one of 900 barricades. [1]

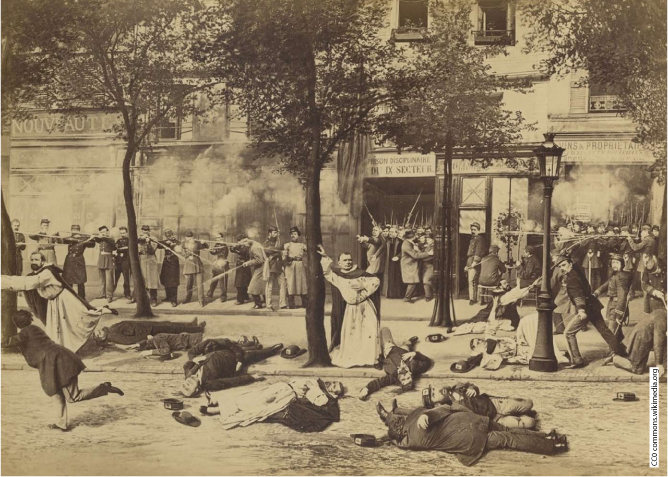

Mass execution in the back yard of the Lobau barracks. [2]

On 21st May, government troops entered Paris through the unguarded western city gate of Saint-Cloud. No more than 20.000 communards faced 120.000 government soldiers. The further the government troops advanced into the proletarian eastern part of Paris, the more brutish they were in their slaughtering. During the so-called Bloody Week, 20–30.000 men, women, old people, children and the wounded became their victims. The next revolution was to be postponed by “killing the fighting part of the population”, as the bourgeois journalist Edmond de Goncourt put it bluntly.

250 buildings were destroyed in Paris that week. Partly by government troops’ bombs, partly set on fire by communards themselves to stop the troops. On 27th May, 147 communards were executed at Père-Lachaise Cemetery, now the memorial for the annual remembrance of the commune. On 28th May, the last barricade fell. People of Paris exhibited their solidarity by hiding many communards; 4–6.000 managed to escape into exile.

House searches, denunciations (400.000 in 3 weeks, 80% anonymously) and arrests followed. The 40.000 imprisoned were mistreated and many died of debilitation and disease. The bourgeois press justified the massacres by defaming the communards as thieves, arsonists and alcoholics. 24 courts-martial, devoid of any rule of law, sentenced the accused to death, imprisonment or deportation. The International Workers Association was banned as a “ringleader”. In 1880 there was an amnesty, the exiles and deportees could return. Many were given a triumphant welcome. As recently as 2016, 145 years later, the Communards were rehabilitated. The fear of the ruling class of the proletariat’s attempts at liberation continues to this day, or as British historian Eric Hobsbawm wrote:

Government soldiers examine the hands of prisoners. Those whose hands were blackened by powder were summarily shot. [3]

Ernest Eugène Appert (1831-1890) provided the police with photographs to identify communards and took pictures of prisoners. He used these pictures for compositions to discredit the Commune, as in this re-enacted scene of a execution by shooting of a hostage.

Although members of the commune’s council tried to prevent such acts, communards shot about 100 hostages during the Bloody Week. This was as pointless as it was understandable given the anger over the government’s massacres. Prosper Lissagaray wrote: “The blind justice of the revolution punishes the first available for all the crimes accumulated by his kind.” [4]

Laurent: Calm down, Marie! Always tell yourself: Imprisoned doesn’t mean dead yet. You’ll see they’ll come back in no time.

Marie: They simply must come home. You can’t be punished for something that is for the benefit of all!

Laurent: I get it, but we have to be brave now. What do you think Matthis would want you to do right now?

Marie: That I keep my chin up and keep going.

[1] CC0 commons.wikimedia.org

[2] CC0 commons.wikimedia.org

[3] CC0 commons.wikimedia.org

[4] CC0 commons.wikimedia.org

[5] Prosper Lissagaray, Geschichte der Commune von 1871, Suhrkamp Verlag 1971, S. 382, 417 und Jaques Rougerie, Paris libre, 1971, S. 258/259 zitiert nach: I. Hartig, Dr. P. Hartig, Die Pariser Kommune 1871, Ernst Klett Verlag, 1975, S. 73/74